Polling of the US election has been widely criticised following the outcome of last Tuesday’s ballot. For weeks in the run-up to polling day the polls were widely reported as saying that the result was too close to call. Not only was there little difference between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris in terms of national vote intentions, but this was also the position in seven “swing” states where the outcome would decide who would win the electoral college vote.

As a result, we were warned it might take days for the winner to be known while the final ballots were counted in what could be razor-thin margins in those swing states.

Yet, in the event, people in Britain woke up on Wednesday morning to be told it was clear that Trump had won. Not only was he ahead in all seven swing states, including in the three where Democrat hopes were highest – Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin – but he also had a decisive lead in the overall national vote. The polls had it seemed once again got it all wrong.

However, now that nearly all the votes have been counted, a closer look at the performance of the polls reveals that – although on average they did somewhat underestimate Trump – the error was less than in 2020. The problem for the polls at this election was that even the smallest error in one direction or the other from the anticipated very tight contest was almost bound to create the impression they had got it “wrong”.

Consider, first of all, the national popular vote. On this the various websites that aggregate the results of countless election polls into a summary average were not entirely in agreement. Most, including Nate Silver’s Silver Bulletin, reckoned Harris was ahead by a point or so. Some, however, including Real Clear Politics, suggested we were heading for a near tie (they had Harris just 0.1 point ahead). The websites that calculate a poll average vary in which polls they include and whether and how they weight them, thereby creating some potential for disagreement about exactly what the polls were saying.

In any event, it now looks as though Trump was only just over two points ahead in the popular vote. His lead has gradually been falling over the past week as more ballots have been counted and, rather than a decisive success for Trump, it looks as though he secured a narrow win in a close contest. In contrast to his first electoral success in 2016, however, he did succeed in winning the popular vote this time around.

So, even if we take the view that the polls were pointing to a one point lead for Harris, the average error in the polls’ estimate of the gap between the two candidates was three points. That compares with a four-point error in 2020 – and is less than half the near seven-point error in the polls’ average overestimation of Labour’s lead over the Conservatives in the UK election earlier this year.

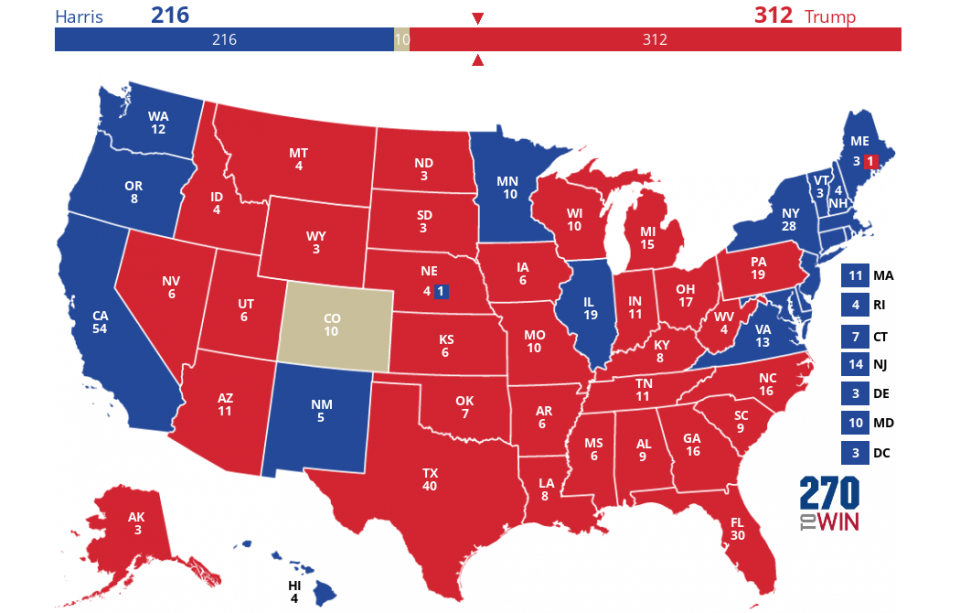

2024 presidential election interactive map

Source: 270 to win

Meanwhile, we should remember there were several polls that did suggest Trump was narrowly ahead. Of the 17 polls that were included in Real Clear Politics’ final calculation, five had Trump ahead, while five anticipated a tie. Only seven actually had Harris ahead. And not included in those numbers were some notably accurate polls by two companies primarily based in the UK, that is, JL Partners (which anticipated a three-point lead) and Redfield & Wilton (which had Trump two points ahead). This was not an election where every polling company got it wrong.

Swing states

But what of those polls in the swing states where Trump swept the board? This surely painted an inaccurate picture? In fact, if anything, these polls were even better than those of the national popular vote.

In two states, Georgia and North Carolina, the polls suggested on average that Trump was one point ahead. In the event, he won by two points in Georgia, and three in North Carolina, errors of just one and two points respectively. The position is similar in the three “blue wall” states of Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania on which Kamala Harris’ hope of victory primarily rested. In the two midwest states the polls had Harris just one point ahead when it was actually Trump who had enjoyed a one-point lead. Meanwhile, in Pennsylvania the two candidates were tied in the polls when eventually Trump won by two points. In short, in each case the error on the lead was no more than two points.

Only in Nevada and Arizona was there a slightly bigger gap between the polls and the eventual result. In Nevada the polls pointed to a tie, but Trump won by three points. In Arizona the polling averages gave Trump a lead of a little above two points, while at present with nearly all the votes counted he has a lead of just under six points – indicating an error approaching four points. Across all seven swing states the average error in the polls was just over two points. This is well below the average error of five in polls of individual states in 2020.

In short, this was no landslide victory for Trump in the swing states. In six of the seven the Republican’s winning margin was no more than three points. This meant, as the pollsters themselves acknowledged could well happen, that rather than the swing states being evenly divided between Trump and Harris, leaving the outcome potentially on a knife-edge for days, just a small error in the polls could see either candidate sweep them all. That in the event was precisely what happened.

Clearly, nobody involved in polling can afford to be complacent about the industry’s performance in this year’s presidential battle. There will be concern that for the third time in a row they have typically – though not universally – underestimated support for Trump. The trouble is, in a close election – and the polls were entirely correct in anticipating that this was going to be a close election – only the smallest of errors can create the impression that the polls have got it wrong.

The truth is that the polls are often at least a little bit out – and we should adjust our expectations of them accordingly.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

John Curtice currently receives funding from the Economic and Social Research Council. He has previously received funding from a variety of charitable and governmental organisations. He was previously President of the British Polling Counci.

EMEA Tribune is not involved in this news article, it is taken from our partners and or from the News Agencies. Copyright and Credit go to the News Agencies, email news@emeatribune.com Follow our WhatsApp verified Channel