How they must be cursing the memory of Yahya Sinwar in Tehran’s corridors of power.

Occasionally in history, one individual tilts the course of events through a single incident: think of Gavrilo Princip’s assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914 or George Washington firing the first shots of the Seven Years’ War with his ambush on French forces in the Ohio Valley in 1754.

The atrocity ordered and masterminded by Sinwar, the late leader of Hamas, on Oct 7 last year has proved similarly momentous, its consequences reverberating well beyond the slaughter grounds of the kibbutzim on Gaza’s borders.

Each wave has weakened Iran, hurting its regional ambitions of dominance, diminishing its stature and prising loose its network of proxies and clients across the Middle East.

The latest, of greater magnitude than most expected, is washing over Syria so fast that it has triggered headlong panic in Tehran.

Amid the dawning realisation that the Assad regime was probably unsalvageable, the Iranian government scrambled to evacuate its diplomats and military officers from Damascus.

So undignified and frenzied was the scramble for the exits it took a while for stunned Middle East observers to realise that Iran was essentially scuttling its decade-long mission to prop up the regime of Bashar al-Assad and abandon the Syrian dictator to his fate.

With rebels on the outskirts of Damascus and rumours that Assad had fled, the last significant element of Iran’s network of proxies and clients across the Middle East seemed to be toppling at breakneck speed.

“Normally empires collapse gradually and then suddenly,” said a Western diplomat with years of experience in the Middle East. “But Iran’s informal empire, its network of influence, is, by historical standards, collapsing very fast. An emergency recalibration is now under way in Tehran.”

Others liken it to the helplessness with which the communist regime in Moscow watched the unravelling of the Warsaw Pact in the late 1980s.

Whether such comparisons are overblown remains to be seen, but Western diplomats, analysts and even members of the Iranian armed forces and political establishment acknowledge that Tehran’s options are dwindling.

If the regime is to shore up its weakening position, they say, Iran will probably either have to adopt pragmatism and enter into genuine, meaningful negotiations with the West – or it will have to race to build a nuclear warhead.

As it scrambles to adjust to the unpredictability of Donald Trump’s incoming administration, it may well seek to do both.

In the past week, the Iranian government has sent out conflicting messages.

IDF

Mohammad Javad Zarif, one of Iran’s 15 vice-presidents, called for negotiations over the country’s nuclear programme, saying that Masoud Pezeshkian, Iran’s new, ostensibly reform-minded president, wanted to “engage constructively with the West” and “manage tensions” with the United States.

At the same time, however, both the United Nations and the US intelligence agencies have concluded that Tehran has rapidly escalated work on building a nuclear weapon.

A report released on Thursday by the office of Avril Haines, the US director of national intelligence, warned that Iran had now accumulated enough material to make more than a dozen nuclear weapons.

The following day, Rafael Grossi, the UN’s chief nuclear inspector, confirmed that Iran was quadrupling its stockpile of uranium enriched to 60 per cent, close to the level needed for a nuclear weapon.

In other words, Iran is close to reaching a juncture at which it may have to decide whether it goes all-in on all-out, at least for a while, on its nuclear programme. Amid evidence of division and recrimination within the regime, it is not a position that Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, wanted to find himself in – not yet, anyway.

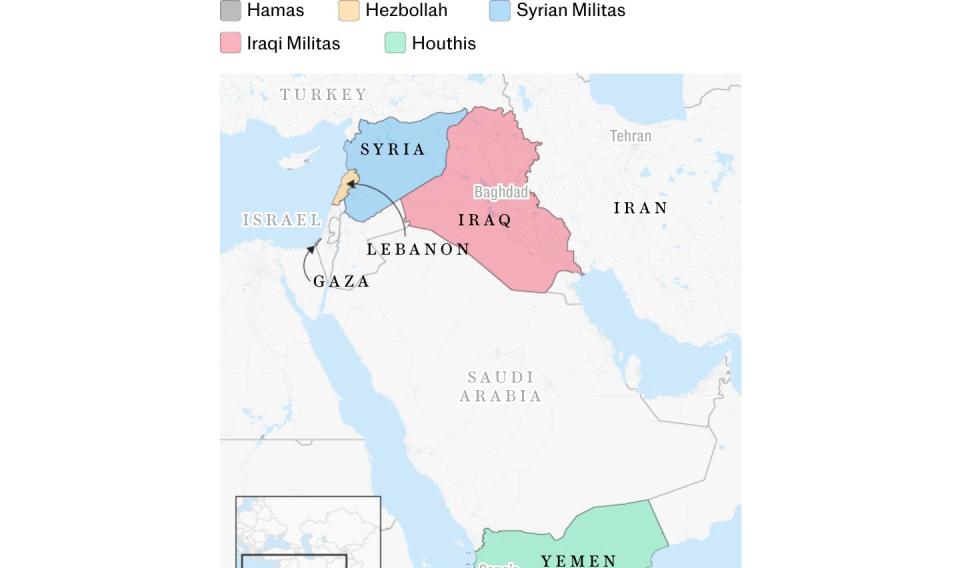

A year ago, the ayatollah was in a much more comfortable position, protected – so he believed – by a network of proxy and allied militias in Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and Yemen. He called them his “axis of resistance,” a “ring of fire” that would not only defend the Shia Muslim world and Iran’s dominance within it but would one day consume Israel, a country he vowed to destroy by 2040.

The proxies, coupled with Tehran’s nuclear ambitions, made Iran arguably the most powerful Muslim state in the Middle East, strong enough to be feared by both Israel and the Sunni Arab countries of the Gulf.

Yet the proxy strategy was always a risky one. It allowed Iran to project power well beyond its borders, to make mischief and wage war at arm’s length and the luxury of deniability, however implausible.

But the groups it supported did not always march to the beat of Iran’s drums, sometimes pursuing agendas that did not always align with Tehran’s wishes.

That was particularly the case with Hamas, a Sunni outfit that may have been beholden to Iran that provided it with arms, cash and training but that appears not to have sought permission from Tehran before launching last year’s attacks.

Sinwar’s massacre unleashed waves of devastation that scythed through Iran’s Middle East policy as an enraged Israel took its vengeance first on Hamas and then on Hezbollah, which had joined the fray.

Instead of its ring of fire engulfing Israel, it blew backwards, scorching through neighbouring states and Iran’s expensively constructed militias until the heat was felt in Tehran itself.

Within little more than a year, Israel had severely weakened both movements, killing both Sinwar and Hassan Nasrallah, the Hezbollah leader, decapitating their high commands and eliminating thousands of their most capable fighters.

The impact was less obvious in Syria initially.

Having nearly been toppled early on in the country’s 13-year civil war, the Assad regime had turned the tide against its assorted foes thanks to Russia’s bombers and Iran’s support on the ground, much of it supplied by Hezbollah, essentially becoming an Iranian client state in the process.

Yet the truth was that, with Hezbollah teetering, a vacuum had opened up in Syria, an opportunity Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, a former al-Qaeda affiliate that broke away in 2017, had spent years training and preparing for.

Sweeping down from its bases in the north, it seized Aleppo, which Assad’s forces had battled for four years to reconquer, in just four days, before capturing Hama, a city that had never previously fallen to the rebels, racing through shattered Homs by Saturday morning and reaching the outskirts of Damascus just hours later.

In no position to save Assad

Yet in the face of this dramatic change of fortune Iran looked on impotently, concluding that, without Hezbollah, it was impossible to save Assad for a second time.

As the situation unfolded, staggered Iranian military insiders spoke of their deep frustration at how the demoralised and underpaid Syrian army, always feeble beyond a handful of elite brigades, had simply turned tail as the rebels advanced.

“Many were surprised by their swift advance and are reluctant to offer full support and send forces this time,” one said. “Some of them say that he [Assad] has had 10 years to prevent this but did nothing because he knew we would be there for him.”

The cost of the Assad regime falling would be huge for Iran. Syria is a vital land bridge that allows it to resupply Hezbollah. A rebel victory would effectively isolate the Lebanese movement, leaving the sea the only route for rearmament, a far from ideal option. Without Syria, Iran is deeply enfeebled.

While it had other proxies in Syria in the form of Pakistani and Afghan Shia units, which Tehran ordered to fall back on Damascus in a desperate attempt to hold the capital, even this was an acknowledgement that neither was capable enough to hold the lime, let alone launch a counter-attack.

Even Iran’s Shia militias in Iraq were of no use. Not only was there not enough time to deploy them, but ordering them to deploy across the border would have further strained ties between Baghdad and Tehran, according to analysts.

Effectively shorn of its axis of resistance, Iran’s horizons have narrowed to a choice between pragmatism and, quite literally, going nuclear.

Pragmatism in the past

Iran has pursued pragmatism in the past, adopting warmer relations with the West during the presidency of Ali Akbar Rafsanjani from 1989 to 1997. With Mr Pezeshkian in office, such a route is more plausible.

The question, however, is whether Mr Trump would be willing to countenance a rapprochement with Iran.

Although fond of making a deal, particularly one he could represent as a swift foreign policy triumph, there are plenty of Iran hawks in his cabinet, said Daniel Roth, research director at United Against Nuclear Iran, an advocacy group headed by Jeb Bush, the former governor of Florida.

“Many of Trump’s cabinet picks are very vocal in their anti-regime outlook,” he said. “You have people like Marco Rubio [secretary of state designate] who has been on the record many times about the real dangers of Iran. So ultimately I think Trump is going to go pretty hard on Iran.”

Sensing Iran’s weakness, Mr Trump is unlikely to countenance anything that appears to be less than the complete dismantling of its nuclear programme.

Tehran’s divided regime therefore faces the choice of whether it wants to be a neutralised Iran on good terms with the West or a nuclear-armed country that could drag the Middle East into all-out war.

As for the incoming Trump administration, it faces a moment of great opportunity – and great danger, too.

EMEA Tribune is not involved in this news article, it is taken from our partners and or from the News Agencies. Copyright and Credit go to the News Agencies, email news@emeatribune.com Follow our WhatsApp verified Channel