It was a warm Monday morning in September when a group of fishermen came across a wooden canoe packed with dead migrants floating 43 miles from Senegal’s capital Dakar.

The migrants, whose bodies were in an “advanced state of decomposition”, are believed to have been making the treacherous 1,250-mile-long journey from Senegal to the Spanish Canary Islands off the coast of north-west Africa.

It was not the first ghost boat to be discovered by fishermen, with more and more desperate migrants cramming onto rickety wooden boats that often fall apart or are blown across the Atlantic before reaching their destination.

Despite knowing the risks, which include death by starvation, dehydration, and drowning, thousands of migrants from Senegal brave the journey every year, and there are no signs of the route slowing down, unlike most other migration journeys in Europe.

ADVERTISEMENT

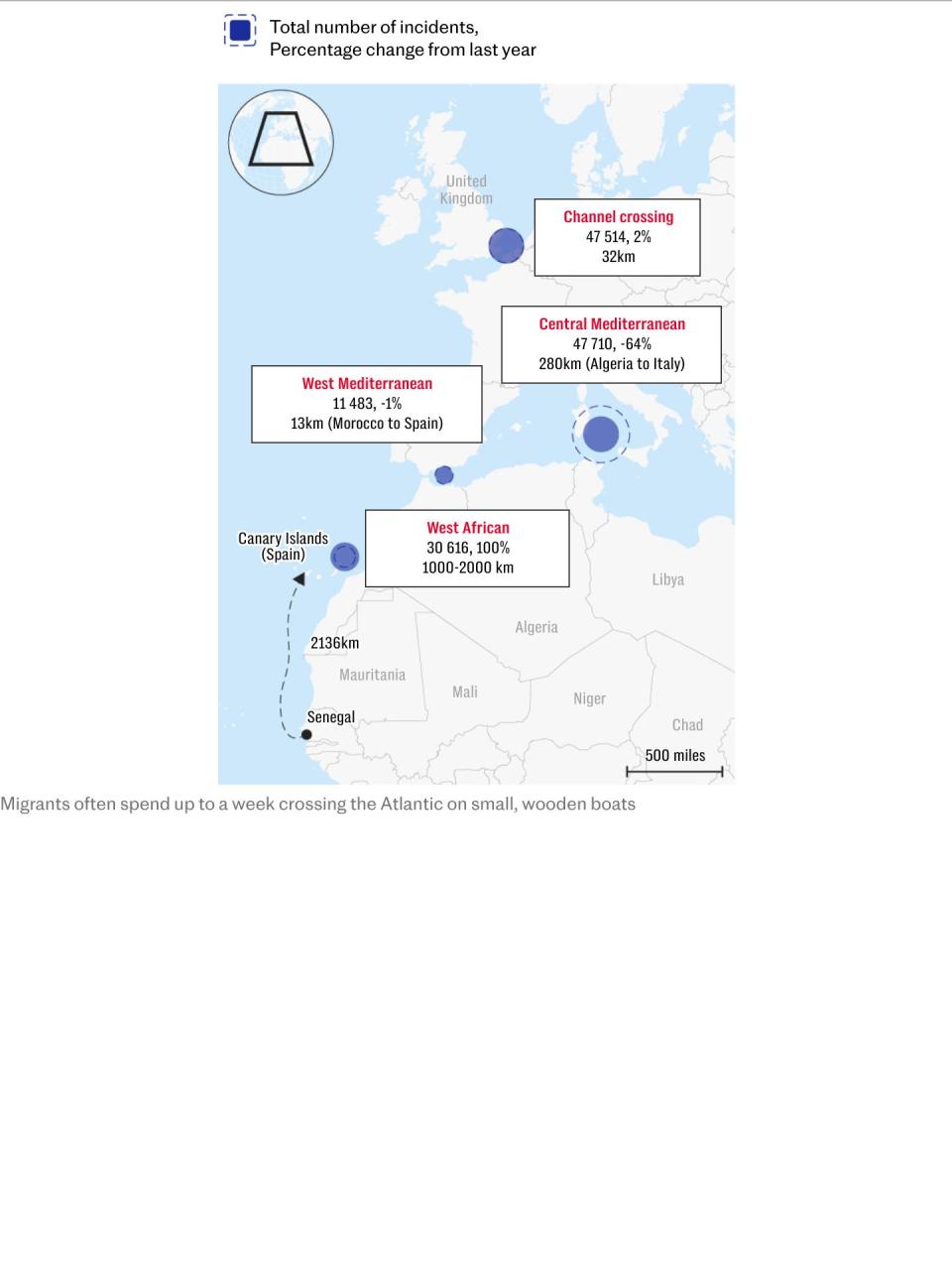

Migration crossings through the west Mediterranean decreased by one per cent in the first nine months of the year, while the central Mediterranean saw journeys plummet by 64 per cent.

But the West African route has surged 100 per cent this year, Frontex figures show, bucking a wider trend.

Ousmane* made the week-long journey from Senegal to the Canary Islands on a rickety wooden boat surrounded by lifeless bodies fearing he would be the next to die.

“Women cry and cry, and so do the men, just because it is so hard to be in the bottom of the boat, surrounded by death. Sometimes you even lose your memory and black out,” Ousmane told The Telegraph.

The young man, who would not reveal his name or age, completed his journey, but fellow passengers weren’t so lucky.

The death toll along the migration route has surpassed more than 800 this year, a 76 per cent increase compared with the same period last year. The real death toll is likely to be even higher, authorities fear.

ADVERTISEMENT

On some journeys, none of the migrants make it to their destination alive. At least 30 bodies were found on that boat off the coast of Senegal in September, according to military authorities.

Judging by the decomposed state of the bodies, the migrant boat had likely been adrift on the Atlantic Ocean for several days before it was found.

Similarly, the bodies of 24 migrants from sub-Saharan Africa were brought to land by Spain’s Maritime Rescue Service at the start of August. Two of those who died were children.

The route has become a major talking point in Senegal, the Canary Islands and mainland Spain.

One migrant who made the journey in a small fishing boat told The Telegraph emotionally: “The number of people that are dying – there are thousands of people losing their lives on the way. Some boats never reach their destination.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The reasons for the surge are complex, according to Inhira García Belda, who works as a social integrator for asylum seekers in Tenerife, the largest of Spain’s Canary Islands.

“We are talking about thousands of people, some of them are looking for a better job in Europe, others are asylum seekers … fleeing due to Macky Sall’s regime,” she said.

Poverty is a major factor driving people out of Senegal, according to Douglas Yates, an associate professor who specialises in African politics at the American Graduate School in Paris.

“A typical Senegalese person eats rice, and if they can get it, a little fish. That’s it… so this kind of poverty, which has been around forever, is driving people away. There are no real jobs or opportunities,” he told The Telegraph.

Mr Yates pointed out that a large proportion of Senegalese migrants making the journey are young men, who are prone to being influenced on social media.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Everybody there has a phone, so they see the rich world, and they look at their own situation and see there are no opportunities. They also see Senegalese people, especially in the capital, getting rich.”

He explained that Macky Sall, who was president of Senegal until March of this year, had promised to “jumpstart” the country’s economy, but for many people, their economic situation worsened – especially after Covid.

Oumar*, who also made the journey from Senegal to the Canary Islands this year, did so for this reason.

“I decided to take the leap because life in Senegal is very, very hard. There’s no work, there’s nothing,” he told The Telegraph.

The Canary Islands have become the favoured destination for migrants, and therefore smugglers, because it is seen as an entry point into Europe, given the Canary Islands’ status as a Spanish autonomous community.

“Spain might not be the final destination,” Ms Belda explains, “but it is the closest European country to the west African coast… they are unable to reach the continent by plane due to visa rejections so the only way to get there is by boat.”

It is not always what migrants expect either, one Senegalese national told The Telegraph.

“The journey was so risky and dangerous, it can’t even be described. The sea was so rough that the captain wanted to return, but others wanted to continue, so a fight broke out,” they explained.

“No matter your situation, it is not worth making this deadly journey because not everyone makes it.”

Senegal’s government announced a 10-year plan in August to tackle illegal crossings and the surge in migrant deaths.

It has also become a political football between the Spanish government and authorities in the Canary Islands, which saw 40,000 illegal crossings in 2023, the highest for three decades.

Fernando Clavijo, president of the Canary Islands, has called on Pedro Sánchez, the Spanish prime minister, to do more to resolve the crisis.

“Every 45 minutes, a migrant dies trying to reach our beaches. This means trafficking mafias are increasingly becoming more powerful,” he said.

Earlier this summer Mr Sánchez ended a tour of Africa in Senegal, announcing a plan to tackle illegal immigration at a press conference alongside Bassirou Diomaye Faye, who replaced Mr Sall in April of this year.

“This region is of the utmost strategic importance for Spain, and we want to contribute to its stability and prosperity,” Mr Sánchez insisted.

But as Mr Yates explained, these sorts of complex political agreements “take time” to come into effect, and there are no signs that the deep-rooted economic issues causing poverty in Senegal will abate under the new regime.

“They have a development plan but it’s not going to increase Senegal’s GDP,” Mr Yates said.

“Senegal can create rich people but it doesn’t make anything… instead they’re doing this kind of symbolism stuff, like anti-colonialism. It’s just rhetoric.”

All this means the number of migrants making the treacherous journey to the Canary Islands is unlikely to fall anytime soon.

Moussa*, despite knowing what he knows about the danger surrounding the journey, still plans to make his way to the Canary Islands next year.

“I want to work, integrate and to have a quiet, peaceful, stable life.”

*Names of migrants were changed for the purpose of this article

EMEA Tribune is not involved in this news article, it is taken from our partners and or from the News Agencies. Copyright and Credit go to the News Agencies, email news@emeatribune.com Follow our WhatsApp verified Channel