On 16 March 2024, British tourist Jake Taylor boarded a ferry to Bali from the picturesque Indonesian island of Nusa Lembongan, after spending several days exploring its remote coves and beaches.

The 26-year-old was enjoying a final holiday before starting a new life in Australia. But on the very same day he was bobbing between the Lesser Sunda Islands, on a train approximately 7,700 miles away travelling from London to Edinburgh, a fare dodger presented his long-expired European Health Insurance Card to a ticket inspector.

The incident set off a chain of events that ultimately saw Taylor wrongly prosecuted for an offence he did not commit, and embark on a lengthy battle to prove his innocence.

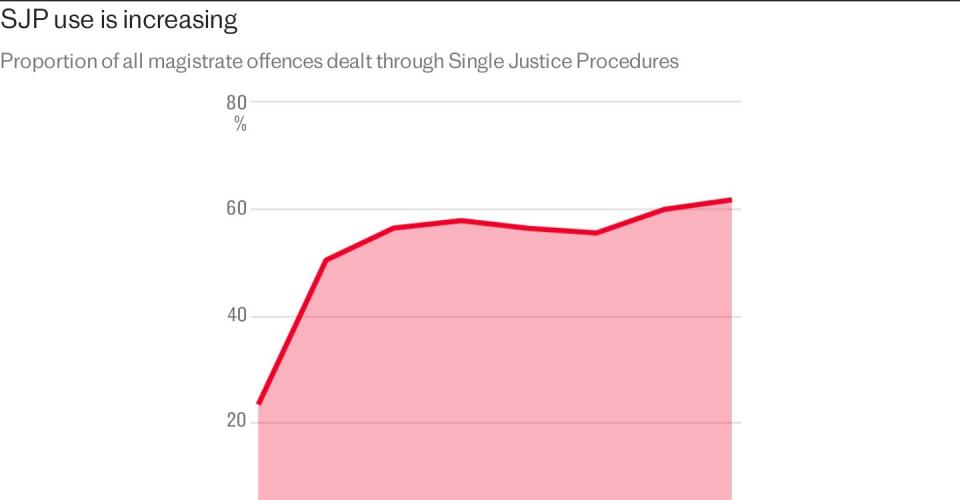

His legal ordeal, while troubling, is far from unique. In fact, Taylor is just one of more than 730,000 people prosecuted under the Single Justice Procedure (SJP) in the year leading up to September 2024, for a range of typically minor offences including transport fare evasion, TV licence breaches, speeding and uninsured vehicles. The process can only be used for low-level and “victimless” offences that cannot result in a prison sentence, but can lead to significant fines and a criminal record if they are not paid.

ADVERTISEMENT

An investigation by The Telegraph has uncovered numerous wrongful prosecutions under the SJP, including cases of mistaken identity and charges against people who have passed away.

There are concerns that many defendants swept up in the secretive, fast-track system do not know they are being prosecuted or are unable to fight cases, with official figures showing that the vast majority of people charged via the system in England and Wales never enter a plea.

Campaigners fear the process is pockmarked by widespread dysfunction, and warn that the true scale of errors and miscarriages of justice is unknown.

Errors and confusion

Since being introduced in 2015, the SJP has allowed charges for minor offences to be dealt with by magistrates and legal advisers in closed courtrooms based on written submissions, unless defendants plead not guilty and demand a hearing.

ADVERTISEMENT

While those in favour of the process view it as clearer and faster for defendants and less costly and burdensome for overloaded courts, critics point to official research warning of errors and confusion.

For his part, Taylor may not have known of his prosecution at all, because all official documentation relating to it was posted to a UK address he had left in March of last year.

When a letter arrived at the London flat in September, as Taylor was settling into life in Sydney, a relative picked it up and offered to send a photo of its contents.

According to London North Eastern Railway (LNER), Taylor had not been in Bali on 16 March, but was in fact on a train from King’s Cross to Edinburgh.

“Important: You have been charged with a criminal offence,” read the document, which claimed Taylor had been caught on the 7.38am service without a ticket. It informed Taylor that under the Single Justice Procedure process, he had three weeks to either plead guilty and pay a large fine, or deny the charge and prepare for a court hearing.

ADVERTISEMENT

The letter did not state why he was believed to be the alleged fare dodger or offer any evidence regarding his identity, aside from a curt statement explaining: “When requested by an authorised person for London North Eastern Railway, Mr Jacob Taylor failed to hand over a valid ticket entitling him/her to travel. Mr Jacob Taylor was issued with an Unpaid Fare Notice. A reminder letter has been sent and [LNER] have received no response or acceptable statement in mitigation [sic].”

Taylor was baffled and scared. He had not been in Britain for months and had no idea how he was going to prove his innocence from Australia.

“Very easily I could have just never heard of this at all, and I’m not sure what would have happened when I went back to the UK,” he says.

“It ended up causing me quite a lot of stress, because if you plead not guilty, you get a court date and you have to attend in person – which seeing as I live in Sydney, presented quite a major problem.”

Mistaken identity

Taylor entered a not guilty plea online and, with the help of relatives, wrote to LNER directly. “Basically, we offered to exchange all the evidence that we had that I wasn’t on the train, for them telling us the evidence they had that it was me,” he says. “Through doing that they told us that someone presented my European Health Insurance Card.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Taylor believes the document had been inside a wallet that was stolen from him more than seven years ago, and would have been long out of date.

“I’m shocked that it was accepted as ID,” he adds. “The fact that I could receive a letter that’s accusing me of a crime off the back of an old European Health Insurance Card being presented on a train is just bizarre to me.”

The prosecution was formally withdrawn by LNER after Taylor offered up a mountain of evidence that he was in Indonesia and could not possibly have been on the train in question, including visas, ferry tickets, credit card transactions and time-stamped digital photos.

LNER told The Telegraph it did not comment “on individual cases”, but only pursued instances of unpaid fares in court as a “last resort” and uses “recognised databases and credit check companies to verify identities”.

Incredibly, the incident involving the rail operator was the second time Taylor had been wrongly prosecuted under the SJP in a case of mistaken identity.

While at university in Manchester in 2016, he was accused of being behind the wheel of a speeding vehicle in London, and the DVLA later admitted an unexplained “clerical error”.

The first he learnt of that prosecution was a letter sent to his parent’s home demanding he surrendered his driving licence. “I ended up having to go to magistrates’ court to plead not guilty, and then it was a gruelling process of trying to find out what was going on,” Taylor recalls.

“Somehow they got their wires crossed and got my identity, my address and requested my driver’s licence to destroy it.

“After I pleaded not guilty they set another court date, but before that my dad had basically managed to get them to admit it was an error on their side, and proved that it was nothing to do with me.”

Taylor says he found fighting the case “really stressful”, adding: “I’m not someone that’s had run-ins with the law or anything like that, so being summoned to magistrates’ court out of the blue, especially when it all felt so unfair because I just knew outright it had nothing to do with me, was a pretty unpleasant experience.”

By the time his second prosecution arose, Taylor says the first case had faded into “a funny anecdote that I would tell people sometimes – ‘I went to court for a crime I didn’t commit’ – and then absolutely bizarrely it happened again. As far as we know, there’s no relation between the two cases. It has just randomly happened twice”.

Pursuing the deceased

Taylor’s extraordinary experience was not the only case of mistaken identity present in a random sample of 50 recent SJP prosecutions sampled by The Telegraph.

A 27-year-old man from Mansfield who was charged with travelling on another LNER service without a ticket in March pleaded not guilty with a submission saying he was the repeated victim of fraud. “This wasn’t me,” he wrote. “I had someone using a picture of my personal ID on several train services in which I appealed and they closed the cases … I have proof.”

Another man, who was prosecuted by Transport for London (TfL) for allegedly pushing through ticket barriers at Leicester Square station in September, also claimed mistaken identity.

Pleading not guilty, the 21-year-old wrote that he was not at the station on that day, adding: “This is not the first time I’ve got letters sent home about this issue, I’ve got friends and family who know my details – anyone could have used them and stolen my identity.”

In other cases, prosecutions were triggered against people who had passed away. In September, the DVLA wrote to an 81-year-old Rochdale woman accusing her of keeping an uninsured vehicle, but it was her daughter who replied saying she had died in June 2023 – nine months before the alleged offence – and the car in question had been sold for scrap shortly afterwards.

In another distressing case, a bereaved father was charged by the police with speeding in Devon, but said it had been his daughter who was behind the wheel of the car at the time.

“When the original notice was sent to me, I passed it on to her to sort out and she assured me that it was taken care of,” the 76-year-old man wrote. “She was found dead on 10 September 2024 whilst in the same car.” The prosecution was later withdrawn.

A DVLA spokesperson told The Telegraph that formal notifications must be made for sold and scrapped vehicles, or those being kept off the road.

“When a vehicle has not been taxed or has no insurance, we will write to the registered keeper multiple times and these letters give them the opportunity to make us aware of any mitigating circumstances,” they added.

“Only when we have exhausted all other enforcement routes will a Single Justice Procedure notice be issued.”

‘Overwhelming complexity’

A report published in December by HM Courts and Tribunal Service highlighted the scale of the problems associated with SJP, revealing that in sampled cases from 2023, only half of police prosecutions for driving offences received a response and the proportion was even lower for other categories.

Just a quarter of TV Licensing prosecutions received a plea, while the figure was 21 per cent for the DVLA, 19 per cent for TfL and only 8 per cent for Merseyrail.

Officials said their research suggests there is “confusion about the difference between the official court stage of a case” and earlier letters, that people are “overwhelmed by the length and complexity” of documents and those from lower-income areas are less likely to fight prosecutions because they “have broader financial concerns that may discourage them from engaging with their case”.

The report also warned of “inaccurate address details” for letters, as well as “technical issues” with the online portal where people are directed to enter pleas.

“Defendant engagement is important to give prosecutors an opportunity to review any mitigations raised and to withdraw the case if they believe it is no longer in the public interest to pursue it,” it added. “There has been media and public concern about vulnerable defendants being prosecuted and examples of defendants pleading guilty while also indicating mitigations related to mental health or other serious conditions.”

In several TV Licensing prosecutions reviewed by The Telegraph, people expressed distress and confusion at the way they were treated by the licensing inspectors.

A mother whose Watford home was visited in August when she was home alone with her child said she let the officer in because she had “nothing to hide”, and that they watched no television or online content requiring a licence.

In her not guilty plea, she said the inspector seemed to be “losing his temper” and accused him of recording information which was “obviously a lie”, adding: “I got a bit worried about me and my child who was at home at that time.”

In another case, a 25-year-old woman from Keighley, in West Yorkshire, accused TV Licensing of “harassment”, writing in a not-guilty plea in November that she did not watch any content requiring a licence and adding: “Your assumed evidence is false and completely inaccurate, and we have already refuted all previous accusations very clearly. We consider this persistent and continual harassment.”

A TV Licensing spokesperson told The Telegraph that officers were trained to be “polite and fair”, and followed set processes when conducting interviews, adding: “TV Licensing has a duty to collect the licence fee from anyone who requires a licence, and we do our utmost to support customers while treating everyone fairly. Our primary aim is to support people in getting licensed so that they avoid prosecution.

“Prosecution is always a last resort, and will only proceed if there is sufficient evidence and any mitigation has been assessed to ensure that the public interest test is met.”

‘Miscarriages of justice’

While the SJP system allows magistrates to send cases back to prosecutors if they receive information suggesting defendants have been wrongly prosecuted or are vulnerable, safeguards rely on people receiving documents, being able to understand them and respond in writing within 21 days to make their case.

If there is no response, magistrates proceed to consider the case without any evidence from defendants, and can find them guilty of the alleged offences and issue large fines.

If people find about a prosecution at a later date – as Taylor did when the DVLA tried to seize his driving licence – they can make a “statutory declaration” that they were ignorant of the proceedings against them, causing the conviction to be overturned and a hearing to be set.

“They send the prosecution notices by normal mail so nobody has any idea how many are actually received by people who are supposed to receive them,” says Penelope Gibbs, director of the Transform Justice charity. “It’s an unfair system and there are miscarriages of justice within it. People don’t understand their rights and they have no access to free legal advice.”

The Telegraph has viewed four recent cases where people were fined £483 each after being prosecuted for allegedly having their feet on train seats, without entering any pleas.

Notices by Merseyrail stated: “It is an offence to interfere with the comfort or convenience of any person on the railway by putting your foot/feet on the seats/seat structure while on the train.”

Several other people charged with the offence contested the prosecutions, including a young woman whose case was withdrawn after she said her actions were not deliberate and that she was “under significant emotional strain” while travelling to a therapy session for sexual abuse survivors.

“I did not intend to break any rules or cause harm,” the woman wrote. “I placed my feet on the seat, not out of disregard for public property or the comfort of other passengers, but because I was distracted and anxious.”

Another woman prosecuted for the same offence pleaded guilty but told how she had been returning from a night shift and suffering from a migraine when caught with her feet up, and was then refused by train station staff when trying to pay the earliest £60 fine. But she was still fined £368.

Other passengers prosecuted for the “feet on seats” offence – including one man on his first visit to Britain – said they did not know it was a crime.

Suzanne Grant, the deputy managing director of Merseyrail, told The Telegraph the fines are enforced to reduce antisocial behaviour on the network’s trains, and that the policy was “clearly advertised” with announcements and posters.

“Our customers tell us that they find people placing their feet on the seat or seat structure in front of them, both unhygienic and on occasion, intimidating,” she added.

A system ‘unfit for purpose’

Gibbs argues the overarching SJP process was set up with insufficient safeguards over how it would operate in practice, while allowing the government to expand it without passing new laws. After going live in April 2015 for vehicle and travel-related prosecutions by the police, DVLA and TfL, it was widened by statutory instrument a year later to cover cases brought by TV Licensing, the Environment Agency, train operating companies and local authorities. In January 2023, the SJP was extended again to cover the prosecution of companies, not just individuals.

“The bit that really concerns me is this lack of participation,” says Gibbs. “It means we have a large swathe of the justice system where it appears that people who are being prosecuted are probably not understanding what’s involved and the consequences. To me, if the plea rate is so low it means that the system is not fit for purpose.”

She adds that while the reasons for low plea rates have not been fully investigated, the evidence suggests that “there are the ones who don’t receive it [the legal documentation], some who put up two fingers and can’t be bothered, and then all the ones – probably the majority – who for a myriad of reasons can’t cope with engaging with the prosecution. It could be to do with having English as a second language, not understanding the form, mental health problems, homelessness – we literally don’t know”.

The SJP received little media attention until the Covid pandemic, when its use to prosecute alleged breaches of lockdown restrictions sparked several high-profile miscarriages of justice.

Journalists have since exposed numerous cases where vulnerable people have been targeted under the SJP, as well as the wrongful application of relevant laws.

In August, it emerged that more than 74,000 rail fare evasion cases had been wrongly prosecuted because train operators had applied the process to the wrong laws. The month before, TfL admitted wrongly telling people caught without a bus fare that they had no legal defence and in 2020, a review found police had been prosecuting people for alleged Covid lockdown breaches under the wrong law.

Gibbs questions how it took years for the legal errors with rail prosecution to be noticed when each case was overseen by a magistrate and a legal adviser. “The government set up no scrutiny mechanisms, the data is poor and there is very little transparency.”

The Ministry of Justice told The Telegraph it was in the process of redesigning the notices sent to people prosecuted under the SJP to ensure they are clear, and that a consultation will be launched early this year to look at enhancing safeguards, improving transparency and driving up prosecution standards.

A spokesperson added: “The Single Justice Procedure was designed to allow low-level offences to be dealt with swiftly, sparing people having to go to court. However, the government is reviewing what more can be done to support vulnerable defendants.”

But Gibbs says the problems with the system have so far been “hidden” and that the government must conduct a “proper review”, warning: “Mitigation about vulnerability only comes out after people have been charged – these prosecutors don’t have the information and don’t even try to get it so they’re prosecuting blind. People need to really look into it in a way they never have.”

Taylor fears his case is the tip of the iceberg, and that other people in his position may not have been able to fight to prove their innocence.

“They will know that a lot of these things fall through when they get challenged, so they should recognise that their process is pretty flawed,” he says. “Some of it feels predatory. Even having not committed a crime, a lot of people would be tempted to pay the fine because of the unknown of what will come down the line. It is just sort of set up to pressure people in a way that feels quite unfair.”

EMEA Tribune is not involved in this news article, it is taken from our partners and or from the News Agencies. Copyright and Credit go to the News Agencies, email news@emeatribune.com Follow our WhatsApp verified Channel