Ten years ago, Camden Prep became one of the first schools in New Jersey’s most infamously flailing district to attempt to resuscitate a chronically poor-performing elementary school.

That same year, Marcus Maurquay started fourth grade at Camden Prep, in a classroom dubbed “The College of New Jersey.” Uncommon Schools, the nonprofit charter operator tasked with turning around Maurquay’s neighborhood school, names each classroom after a college in an effort to raise postsecondary expectations.

The state had recently taken control of K-12 schools in Camden, a city then-Gov. Chris Christie had called “a human catastrophe.” Barely 20% of students could read at grade level, and fewer than half graduated high school. Twenty-three of the city’s 26 schools were among the lowest-achieving in the state.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Over the next few years, like many other urban districts beset by plummeting property values and spiking rates of poverty and crime, Camden welcomed several new public charter schools and turned over its most chronically failing schools to education nonprofits, which rebranded them as renaissance schools.

Today, Camden is considered one of the country’s most innovative districts. More than two-thirds of students attend public charter or renaissance schools, enrollment is climbing and the city is steadily, if incrementally, closing performance gaps among low-income kids.

To be sure, the school system has a long way to go: The majority of students still don’t read on grade level, chronic absenteeism is on the rise and budget constraints present a serious challenge.

How Is Camden’s Innovative School System Moving the Needle for Students?

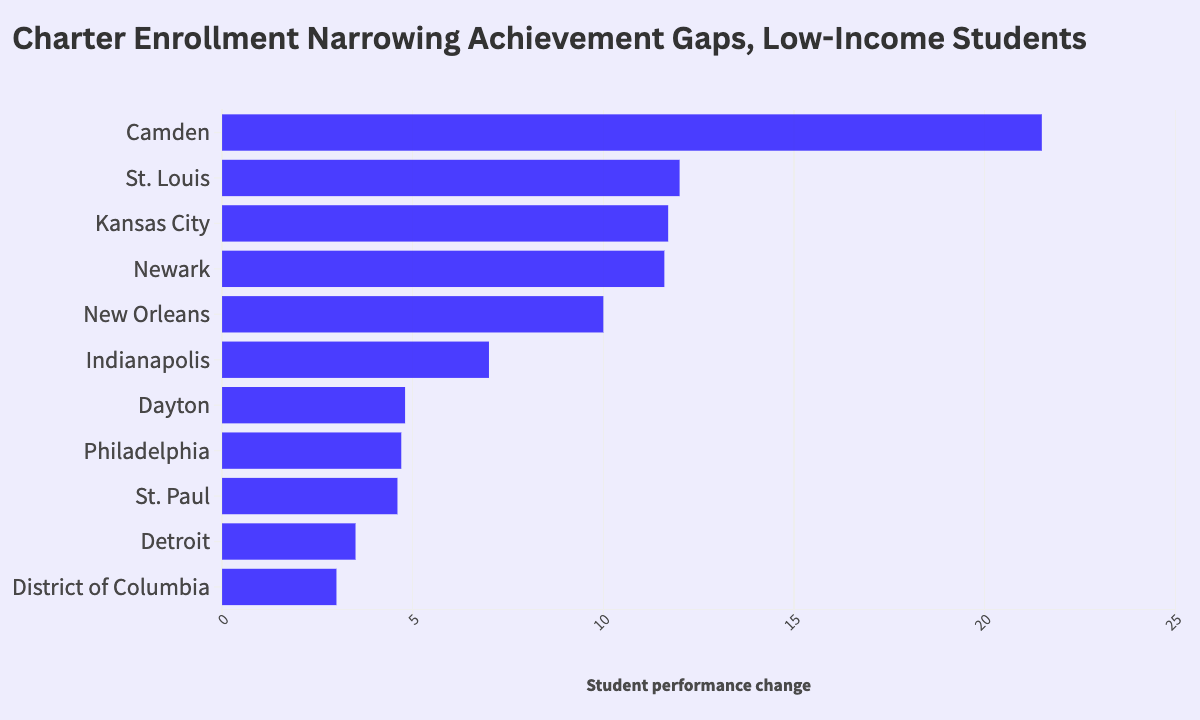

But new research shows that low-income kids in Camden boosted their proficiency on state standardized exams by 21 points between the 2010-11 and 2022-23 school years. And in doing so, they closed a longstanding performance gap with peers statewide by 42%.

Maurquay was among those who benefited from this evolution. And in a full-circle testament to just how far the city has come, in August he stepped onto The College of New Jersey’s real-life campus as a freshman – a first-generation college student with a full scholarship.

Camden isn’t the only low-income city where students in charter or renaissance-like schools are closing learning gaps with their more affluent peers.

A new report from the Progressive Policy Institute finds that over the last decade, low-income students in large districts that aggressively expanded public school choices have started to catch up to their peers statewide — and performance levels are rising in both charter and district-led schools. In fact, in the 10 districts with the highest percentage of students enrolled in charter schools, low-income students citywide closed the gap with statewide test score averages by 25% to 40%. (The analysis doesn’t include New Orleans, where 100% of district students attend charter schools.)

“We just wanted to … see if the impact was spilling over,” says Tressa Pankovits, co-director of PPI’s Reinventing Public Schools project. “We were really surprised by the amount of gap closure between students citywide and the statewide averages. It wasn’t just single digits. It was well into double digits.”

The analysis examined data from cities across the country where a majority of students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, and where at least a third of kids attend a public charter or charter-like school. The researchers used average standardized test scores from third through eighth grade.

Interactive: See How Student Achievement Gaps Are Growing in Your State

The researchers underscored that the one-third proportion is not a guaranteed or proven tipping point, but that in nearly every case where those schools reached or exceeded that enrollment level, academic growth rose across the city for all low-income students.

“There has been slow but steady progress in Camden,”says Giana Campbell, executive director of the Camden Education Fund. “Sure, there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done, but when we look at where the city was 10 years ago, we’re really, really encouraged by the progress that we’re seeing across the city.”

“We knew a time in Camden where we didn’t have this diversity of school types and progress wasn’t what it is today. The proficiency scores in Camden in 2010 were just criminal. There wasn’t much lower we could go,” she says. “And so I don’t think it’s a coincidence that being one of the most innovative school systems, with all these different school types, that we’ve been able to see the progress that we have today.”

New Jersey is home to another standout in PPI’s report: Newark, where 35% of students are enrolled in public charter schools and the performance gap closed by 45% across the same 12-year period.

Missouri boasts two school systems making similar progress. In Kansas City, where 46% of students are enrolled in public charter schools, the performance gap between low-income students and all students closed by 31% between the 2010-11 school year and 2022-23. And in St. Louis, where 39% of students are enrolled in public charter schools, the performance gap closed by 30%.

Hannah Lofthus, founder and CEO of the Ewing Marion Kauffman School, says the report’s findings reflect what she has experienced over the last 15 years in Kansas City, which offers enrollment in neighborhood schools; charter schools; “signature” schools, which focus on college preparation; and career and technical schools. Kauffman consists of two charter middle schools and a charter high school.

“We said, ‘How can we figure out what works for kids and then replicate that,’” she explains. The daughter of two public school teachers, she says collaboration among the various types of schools in the city has been key to the big gains posted by low-income students. “We have kids coming to us in fifth grade 15% proficient in reading and math, and they leave somewhere around 70% proficient.”

Pankovits cautions that the analysis shows correlation, not causation. And while the increases demonstrate significant academic growth, proficiency is still low for the majority of students in these districts.

But Pankovits also says the report refutes often-cited claims that charters drain district schools of the best students and resources, to the detriment of those left behind. Instead, she argues, the increasing enrollment in charter schools creates “a positive competitive dynamic,” and that the report’s findings should bolster policymakers’ confidence in the potential for fixing underperforming schools for all students in low-income communities.

Effectively, a rising tide lifts all boats: When looking only at traditional district schools in Camden, for example, low-income students closed 35% of the proficiency gap during the same decade-long window, versus 42% for the district overall.

Like Camden, Indianapolis has traditional district schools, charters and so-called innovation schools that it uses to drive its academic turnaround. The report found that in the city, where 58% of students are enrolled in public charter schools or innovation schools, the performance gap between low-income students and all kids statewide closed by 23% between the 2010-11 and 2022-23 school years.

In Indianapolis, Charter Schools ‘Move the Needle’ on Achievement, Study Finds

“The report confirms what we’ve seen in Indianapolis for a long time,” says Brandon Brown, CEO of the Mind Trust, a nonprofit that supports the city’s charter and innovation schools. “And a lot of the evidence shows that the growth of high-quality charter schools does not come at the expense of the school district. It really tends to lift many of the outcomes for schools of all types.”

“I think we’ve shown in Indianapolis that it’s hard and it’s not a straight line and we don’t always agree, but when these systems work together, the chances that kids are going to benefit will go way up,” he says. “And I think we’ve seen that here very clearly.”

The report comes as America’s schools are still trying to chart a recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, which set students back academically and decreased enrollment. A new report from National Alliance for Public Charter Schools finds that over the past five years, charter schools gained nearly 400,000 students, while district schools lost 1.75 million. Hispanic and Black families are increasingly choosing charters, the report shows, with Hispanic enrollment growing 18 times faster in charters than in district schools.

In Indianapolis, enrollment is on the rise, and at the highest point in more than a decade — a fact Brown credits to the public school choices that families have. For the first time, he says, parents from adjacent school districts are opting into the city system.

“Large urban districts across the country that are facing massive enrollment declines should look at Indianapolis and see the collaboration to create high-quality options for families, and see it as a way to mitigate negative impacts on enrollment,” Brown says. “When system leaders can work together, it tends to grow enrollment, and that stands in stark contrast to a lot of school districts across the country.”

Disclosure: The Mind Trust provides financial support to The 74.

EMEA Tribune is not involved in this news article, it is taken from our partners and or from the News Agencies. Copyright and Credit go to the News Agencies, email news@emeatribune.com Follow our WhatsApp verified Channel