Mozambique’s new President Daniel Chapo has been sworn in at a low-key ceremony in the capital, Maputo, more than three months after heavily disputed elections.

Most businesses in Maputo were shut after defeated presidential candidate Venâncio Mondlane called for a national strike to protest against Chapo’s inauguration.

Chapo won the election held in October with 65% of the vote, extending the 49-year-rule of the Frelimo party.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Mondlane – who contested the election as an independent – came second with 24% of the vote. He rejected the result, saying it was rigged.

Mondlane called for a strike on inauguration day “against the thieves of the people”.

Both of Mozambique’s leading opposition parties – Renamo and MDM – boycotted the swearing-in ceremony because they too do not recognise Chapo as the rightful winner.

Even those in Mozambique who do wish Chapo well openly question his legitimacy.

“Chapo is someone I admire greatly,” civil society activist Mirna Chitsungo tells the BBC.

“I worked with him for four years – I am familiar with his willingness to act, his openness to dialogue, and his readiness to follow recommendations from civil society on the ground.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“However, he is assuming an illegitimate power. This stems from a fraudulent electoral process… He is taking power in a context where the people do not accept him.”

‘He will face many enemies’

In addition to winning over a hostile public, Chapo will also have to deliver the economic turnaround and halt to corruption that he promised on the campaign trail.

“Chapo will face many enemies because it looks like Mozambique is run by cartels, including cartels of books, cartel of medicines, cartel of sugar, cartel of drugs, cartel of kidnappings, mafia groups,” says analyst and investigative journalist Luis Nhanchote.

“He needs to have a strong team of experts, willing to join him in this crusade of dismantling the groups meticulously,” he adds.

Advertisement

Advertisement

More in World

“But first, he has to calm down Mozambicans and do all in his power to restore peace in the country.”

Daniel Francisco Chapo was born on 6 January 1977 in Inhaminga, a town in Sofala province, the sixth of 10 siblings. This was during Mozambique’s civil war, and the armed conflict forced his family to move to another nearby district.

His secondary schooling in the coastal city of Beira was followed by a law degree from Eduardo Mondlane University then a master’s degree in development management from the Catholic University of Mozambique.

Now married to Gueta Sulemane Chapo, with whom he has three children, Chapo is also said to be a church-going Christian and fan of basketball and football.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Many current and former colleagues describe Chapo as humble, hard-working and a patient leader.

Mozambicans who say the election was stolen have been protesting for months [EPA]

Ahead of becoming the ruling Frelimo party’s presidential candidate, he had been a radio and television host, a legal notary, university lecturer and provincial governor before rising to the post of Frelimo general secretary.

Speaking at his recent birthday celebrations, Chapo himself acknowledged the daunting challenge awaiting him as president.

“We must recover our country economically… it’s easy to destroy, but building is not an easy task.”

National reconciliation, creating more jobs, reforming electoral law and decentralising power are top of his agenda, he said.

Advertisement

Advertisement

But how successful can he be without much of the country behind him?

At the very least he will mark a change from outgoing President Felipe Nyusi, whom Ms Chitsungo says many Mozambicans will be happy to see the back of.

“Chapo is a figure of dialogue and consensus, not one to perpetuate Nyusi’s violent governance style. He has the potential to negotiate with Mondlane.

“While Chapo may not fully satisfy all of Mondlane’s demands, I believe he could meet at least 50% of them,” adds Ms Chitsungo.

Mondlane – a part-time pastor who insists he was the true winner of the polls – is reported to be sheltering in one of Maputo’s hotels after returning from self-imposed exile.

Advertisement

Advertisement

It is not known what security protection he has there, nor who is paying for it.

He alleges that last week, while touring a market in Maputo, a vendor in his vicinity was shot, echoing the murder of two of his close aides in October.

As the mastermind of nationwide protests against the disputed election result, he has come to be seen by many as a voice for the voiceless. Yet, at present, the president-elect’s camp is not engaging him publicly.

Nonetheless, listening to the public’s grievances and demands, and sometimes ignoring the commands of his ruling Frelimo party, will be key to Chapo’s success, analysts have told the BBC.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Finding some way of engaging constructively with Mondlane would undoubtedly provide a boost, they say.

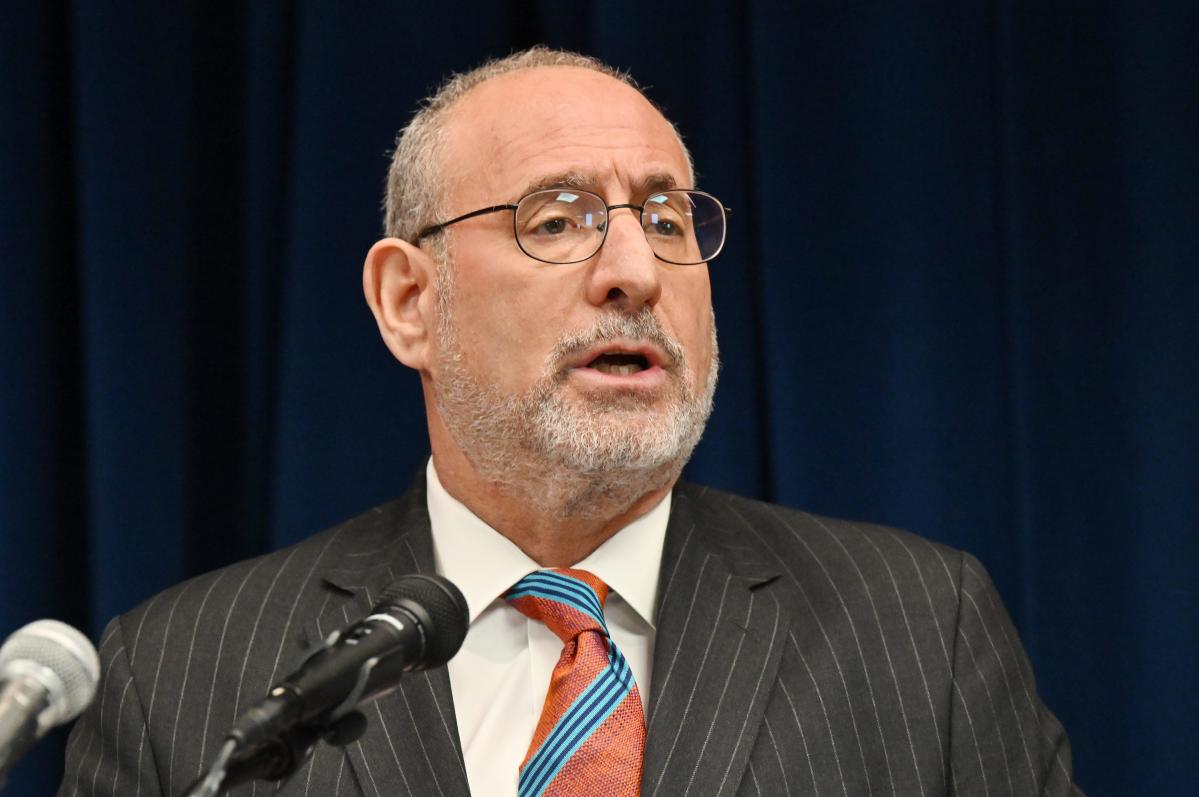

Venâncio Mondlane is the biggest thorn in the president-elect’s side [Reuters]

Winning the public over may also require Chapo to say no to “fat salaries for the elite and fringe benefits, some of which are 10 times higher than Mozambique’s minimum wage”, argues Mr Nhachote.

Plus, if Chapo is to have any chance of bringing an end to the broader political crisis, he will require support from others to make lasting, structural change, argues prominent clergymen Rev Anastacio Chembeze.

“Perhaps we should remain sceptical of one single person to solve the challenges of Mozambique – change must start within the system itself.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“We should strive for a separation of powers within the state apparatus, the international monopolies have huge interests in the country, and we have serious ethical issues within the political elites to address it.”

Once in office, Chapo should sack the country’s Police Chief Bernadino Rafael, analysts have told the BBC. He denies any wrongdoing but is regarded by some as the mastermind behind the brutal response to the post-election protests.

They say they want him replaced with a successor who “respects human rights” and follows legal and international standards. Another suggestion analysts have touted is for a new attorney-general to be brought in.

Chapo will be the first president of Mozambique who did not fight in the independence war.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“He is part of the new generation. Part of his background is completely different from his predecessors – he was born in a country liberated by them,” says Mr Nhachote.

“If he wants to make a real mark on history, he has to challenge those past icons. If he can’t [manage that], I am sure that he will only run for one term.”

You may also be interested in:

[Getty Images/BBC]

Go to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica

BBC Africa podcasts

EMEA Tribune is not involved in this news article, it is taken from our partners and or from the News Agencies. Copyright and Credit go to the News Agencies, email news@emeatribune.com Follow our WhatsApp verified Channel