Terry Scott is one of those comedians whose name is somewhat forgotten, but from the 1960s to the 1980s he was rarely off the screen in a series of sitcoms and sketch shows. These culminated in a long partnership with June Whitfield, usually cast as his long-suffering spouse, most notably in the BBC sitcom Terry and June.

He prided himself on his work in farce such as Run For Your Wife and A Bedfull of Foreigners. But it was in pantomime that his particular qualities – high energy, infectious twinkle and spluttering indignation – shone the brightest.

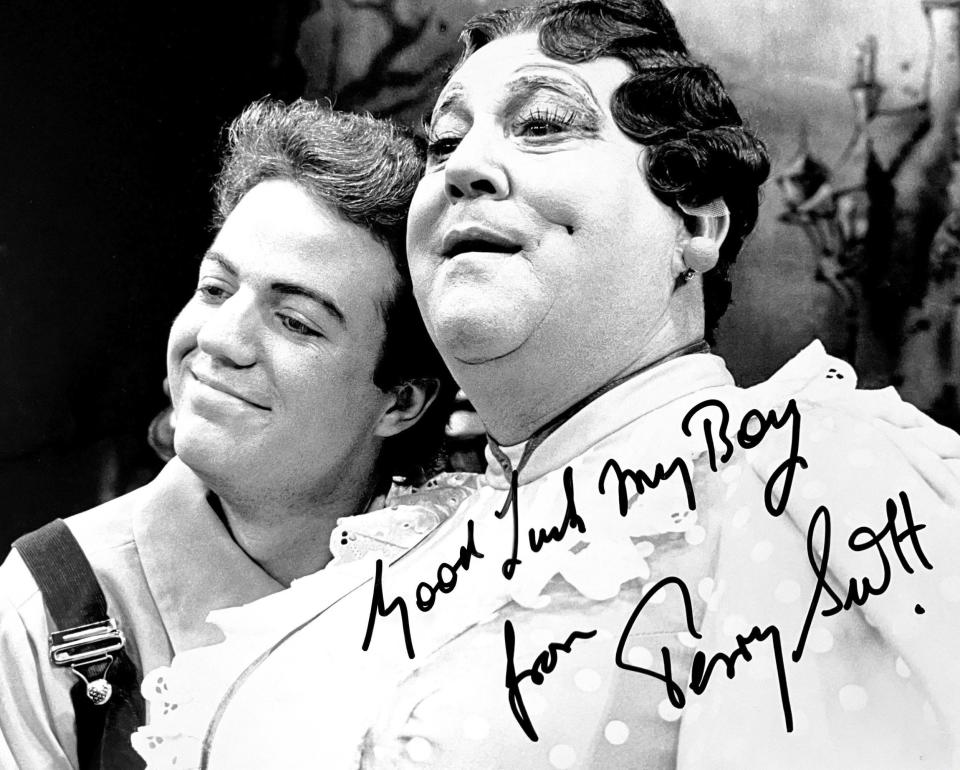

And it was in panto that I first saw him – Aladdin at the London Palladium. I was seven years old and apparently I didn’t utter a word all the way home. My fate was sealed. All I could think of was the rotund comic who made such an unforgettable Widow Twankey.

Following that theatre trip, I never lost the acting bug. After various school plays I found myself in the Cambridge Footlights, performing at the Edinburgh Fringe, where, in 1985, I did a comic monologue on Russell Harty’s late-night chat show. As luck would have it, watching television that very night in deepest Godalming was Terry Scott. The next day I was summoned to meet him at his agent’s office just off the Strand. He must have ejected the agent as he was in pride of place behind the desk, hair smarmed down, pastel jacket and slacks to the fore.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I’m doing panto in Bath this year with June. D’you want to be my feed?”

“Your feed?”

“It’s Jack and the Beanstalk, so you’ll be Simple Simon. You set ’em up, I knock ’em down. Any gag’s 90 per cent about the feed, so you better get it right.”

“You can understudy me too if you like,” he said, getting up. “I never miss a show so you won’t go on, but you’ll learn a lot.”

When we began rehearsals, he proved a hard task master – watching me and being critical. “Why are you doing it like that? No! Turn this way! What’s that? It’s meaningless! You’re not ponging [stressing] the right word, you fool! That won’t get a laugh. You might have got away with it in the ‘Footlights’ [the word uttered with withering disdain], but not in my show, mate.”

Terry was a complicated man: instinctively liberal with reactionary tendencies, anti-intellectual with a reverence for opera and ballet, a debunker of pretension in others yet often seen with a coat draped over his shoulders, cane in hand and gold medallion adorning his barrel chest.

ADVERTISEMENT

During the run, we were all invited to Bath’s Guildhall for drinks with the Mayor. Signing the visitors’ book, I noticed a florid autograph above mine: “Terry Scott, Actor and Philosopher”.

And in some ways he lived up to this boast. One rainy afternoon I bumped into him at the stage door, sifting through his fan mail. “What a rotten day,” I grumbled. He thought for a moment. “You see, that’s the difference between us. Yes, the sky is grey. But to me, grey’s a beautiful colour.” I went straight to June’s dressing room. “You’ll never guess what he’s just said!” I recounted the story and she rolled her eyes. “He wouldn’t try that with me because I’d just say, ‘No Terry, it’s a bloody awful day.’”

I was the panto apprentice who couldn’t answer back, of course, whereas the two leading ladies – June and Avengers star Honor Blackman viewed him with the same weary resignation. I remember chatting to Honor in the wings one night, telling her about a book that Terry had lent me. “What’s it called?” she drawled, “‘The Art of Comedy by Terry Scott’?”

But he was a great Dame. Why? His timing was immaculate, his rapport with the audience instant. And then there was his striptease – a masterclass in physical buffoonery.

ADVERTISEMENT

But it wasn’t all comedy – Terry liked to tug at the heartstrings too. After a knockabout farmyard scene, Dame Trot prepared Daisy the Cow for market. This climaxed in Terry pinning a straw hat on Daisy’s head, the excruciating pain causing the cow to stagger a little. In a curious mix of laughter and tears, an overweight man in a frilly pinafore somehow made us care about an old woman and her bovine best friend. The spotlight faded, Terry’s voice cracked and, in the audience, the tissues came out.

This ability to switch between comedy and tragedy came easily to Scott. He maintained that every panto storyline affords two or three opportunities for heartbreak, and he certainly knew how to exploit them. And it was obvious that his personal tragedies – the loss of an only brother when he was six, a catalogue of ill-health (he often wore a neck brace to rehearsals), his deafness, a complicated marriage – all this was mined and unexpectedly glimpsed on stage.

We took the show to Guildford the following year. I hadn’t ever gone on for him as the Dame, but in the penultimate week of the run he had a bad cold and was losing his voice. After the Saturday matinée I went to find the Musical Director in the band room. “Could we possibly sing through Terry’s songs, just in case?” I asked. He continued reading his newspaper. “I wouldn’t bother.” “Yes, but – “ He lowered the paper. “Listen son, this show doesn’t happen without Terry Scott.”

As the half hour call sounded over the tannoy, my dressing room door flew open and the Company Manager charged in. “You’re on!”

ADVERTISEMENT

Of course, I had no dame costumes of my own, and I was considerably slimmer than Terry. So the wardrobe mistress wrapped a roll of foam rubber round me and, miraculously, everything fitted – all 14 frocks. A wig was clamped on my head and I was standing in the wings about to enter when I felt a tap on my shoulder. I turned round and there was Terry. “Just be full of fun,” he whispered, “and you’ll be all right.” The band played, the follow spot kicked in and the Musical Director looked up at me from the pit with more than a hint of panic in his eyes.

Terry returned the following week, but he became increasingly irritated by everyone telling him how proud he must be of me. I wasn’t in his league of course, but I’d done my best and everyone assumed he’d be pleased. It was much more complex than that.

At the cast party a few days later we were all celebrating after the final show. I’d always got on well with Terry’s wife but that night she was cool with me. “I hear you were very… efficient the other evening,” she said. The room went silent. “Gosh,” I said, taken aback. “‘Efficient’.” Terry’s eyes flashed with rage. “Well? What’s the matter?” he blurted out. “A star wasn’t born overnight, you know.”

I am now a theatre and opera director, and for all Terry’s harsh words, I still find his instructions very useful. “Don’t pong that word! Drive to the end of the sentence! Just play the truth!” – I bang on about all these things in the shows I direct.

I can see that he was, in effect, the drama school training I never had, and a valuable antidote to the rarefied world of Cambridge student theatre.

Terry died in 1994, at the age of 67. He wasn’t one to keep in touch, but it was clear after I stood in for him that a line had been drawn. He had given me an opportunity and yet somehow he resented me. Nowadays aspects of his behaviour wouldn’t be tolerated, quite rightly. But even so there was something heroic in his battles – with his demons, with his audience and with me, and I count myself fortunate to have been in the right place at the right time.

Christopher Luscombe’s production of The Rocky Horror Show is currently on tour in the UK. His production of L’elisir d’amore opens at Garsington Opera in May

EMEA Tribune is not involved in this news article, it is taken from our partners and or from the News Agencies. Copyright and Credit go to the News Agencies, email news@emeatribune.com Follow our WhatsApp verified Channel