William Freeman was destitute, disabled, nearly friendless and without future prospects, all before his 21st birthday.

He’d just served five years in Auburn State Prison for stealing a horse; he swore he didn’t do it. Unceasing prison labor had brought him debilitating injury but not even nominal compensation. All he got when he left the prison in September 1845 was two dollars, ideally to catch a stagecoach or train out of the city.

Freeman had few advantages, but he was determined.

“I have worked five years for nothing, and they have got to pay,” he said over and over. What may have sounded at the time like empty muttering soon proved to be the kernel of a gruesome quadruple murder and the subject of a new book, “Freeman’s Challenge.”

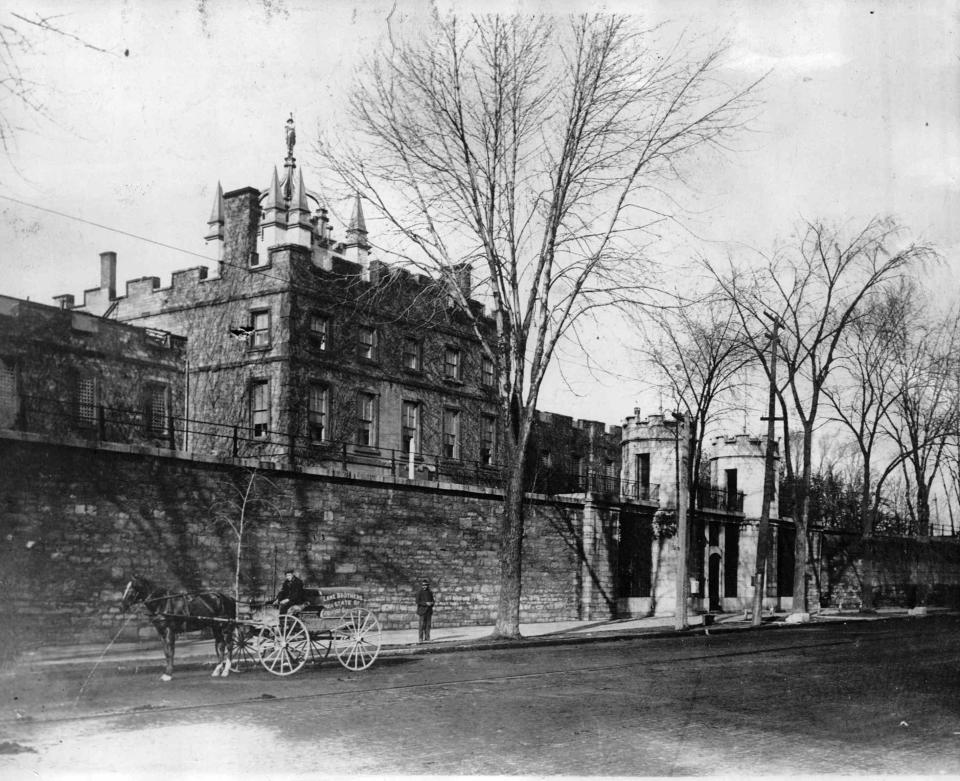

Author Robin Bernstein, a historian at Harvard University, uses Freeman’s case to interrogate the economic and racial foundations of the early Northern carceral system. The state prison in Auburn, founded in 1817 and operated continuously to the present, was one of the most influential prisons in the United States.

At issue was the very purpose of incarceration. Advocates elsewhere posited rehabilitation or punishment. Auburn found a third way: profit.

“Unlike their counterparts who built prisons in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and other nearby states, Auburn’s leaders had no discernible interest in reform,” Bernstein writes. “They viewed a prison as a vehicle by which to soak up state funds, build banking, stimulate commerce, manufacture goods, and developed land and waterways. In short, they reimagined the prison as an infrastructure for capitalism.”

The role of unpaid convict labor

By the time 15-year-old Freeman was incarcerated in 1840, the system was working exactly as designed. The city of Auburn had swelled, and nearly the entire local economy was dependent on the prison in one way or another.

Unpaid convict labor factored in prominently. Freeman, whose grandfather had been enslaved by the city’s founder, rebelled ferociously against prison rules that forbade talking, looking people in the eye or otherwise interfering with the manufacturing apparatus. He was beaten repeatedly while incarcerated, including one particularly brutal incident that left him deaf and, perhaps, mentally disabled for the brief remainder of his life.

More: Rochester man wrote first Black prison memoir from Auburn

Again and again after his release, Freeman demanded restitution for his work in the prison, to no avail. His constant refrain — “they have got to pay” — became distinctly threatening.

About six months after his release from prison, Freeman walked three miles south of Auburn, eventually coming to a house owned by a local white family for whom he briefly had worked. He knocked and was let in, then proceeded to stab five inhabitants, killing four.

Among them were a pregnant woman and a 2-year-old boy.

The crime shocked the region. When he was captured the next morning, Freeman gave an explanation that was consistent but seemingly insufficient: “(He) said the state owed him for five years’ work, and they had to pay him, or someone had got to pay him.”

In this sentiment, Bernstein finds an eloquent if unexpected indictment of the brutal conditions at Auburn State Prison as well as the economic basis of the institution and the city itself.

“Freeman saw what anyone could see if they cared to look: the state and the prison were operating through each other, both politically and economically,” she writes. “The resulting violence could not be confined to the prison, no matter how thick the walls.”

That was not the popular view at the time. White journalists, prosecutors, clergymen and the public at large rejected Freeman’s explanation and proposed others. The crime was proof of inherent Black savagery, they said — but not insanity, a defense that might have kept Freeman from the noose.

William Seward steps into the story

Freeman was defended by Auburn’s most prominent citizen, former New York Governor and later Secretary of State William Seward. He conceded Black people’s inherent deficiencies but placed the blame for the crimes on white society for having failed to raise Freeman and the rest of Auburn’s small Black population from their natural debased state.

“Prosecution and defense agreed, then, that Black people needed white assistance and supervision — without which they would commit crimes,” Bernstein writes. “In both narratives, Freeman’s murders proved that white people needed to control Black lives.”

A jury determined that Freeman was sane enough to face the murder charges and another one quickly convicted him. He avoided execution only by dying in prison in August 1847, age 22.

Freeman’s critique was largely ignored during his life but was taken up by Frederick Douglass, who called his demand for compensation a “righteous demand.”

Bernstein agrees and fits the 180-year-old story into a modern-day call for prison abolition.

“Prison as we know it was constructed, challenged, defended, adjusted, and re-entrenched by individuals working in concert,” she writes. “By understanding their actions, we can imagine alternatives.”

— Justin Murphy is a veteran reporter at the Democrat and Chronicle and author of “Your Children Are Very Greatly in Danger: School Segregation in Rochester, New York.” Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/CitizenMurphy or contact him at jmurphy7@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: ‘They have got to pay’: Book finds prison critique in quadruple murder

EMEA Tribune is not involved in this news article, it is taken from our partners and or from the News Agencies. Copyright and Credit go to the News Agencies, email news@emeatribune.com Follow our WhatsApp verified Channel