Vice President Kamala Harris has spent more than a decade advocating for Black, Hispanic and impoverished communities struggling with pollution — an insurgent segment of the environmental movement that never entirely warmed up to President Joe Biden.

Now her allies hope her long-running work on the issue can mobilize a pocket of grassroots enthusiasm among Democrats and independents that might’ve otherwise sat out the election. But it has also drawn years of blowback from Republicans, including misleading claims that she has supported racial preferences that would harm white Americans.

That theme could assume a larger role in an election where the GOP has struggled to find a consistent, but non-offensive, line of attack against the nation’s first Black, South Asian and female vice president. The intersection of green policy and social justice also offers clues to how a Harris administration may differ from Biden’s — and is one arena where she has a longer track record than her boss.

Biden has weighed how race, poverty and a lack of political power have left some communities disproportionately exposed to pollution, an approach referred to as environmental justice. That history has guided many of his policies, and last year, he created a White House office devoted to the issue.

But he has also faced complaints from activists that the administration is failing to properly staff those initiatives and greenlighting some fossil fuel projects that threatened rural or Indigenous communities. Harris, meanwhile, despite facing some hesitancy among green groups in her home state wary of her record as a prosecutor, has embraced the cause since her time as San Francisco district attorney, a job she held from 2004 to 2011.

“The environmental justice community will be solidly behind Kamala,” said Beverly Wright, founder of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice and a member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, adding that people in the movement know and trust Harris.

“I hear comments like ‘She has to prove herself,’” Wright said. “What? Are you kidding?”

A poll released in June from an arm of a health care trade association advocating to address environmental justice suggests the issue appeals to a majority of people, regardless of ideological lines, generations and income. But some congressional Republicans have blasted Harris’ remarks about equity.

After Hurricane Ian devastated Florida in 2022, Republican Sen. Rick Scott assailed Harris for comments saying she supported “giving resources based on equity.”

Harris, responding to a question about the federal response to disasters such as Ian, had noted during a forum in Washington that it is “our lowest income communities and our communities of color that are most impacted by these extreme conditions.”

She added, at the time: “We have to address this in a way that is about giving resources based on equity, understanding that we fight for equality, but we also need to fight for equity; understanding that not everyone starts out at the same place.”

A few days later on CBS’s Face the Nation, Scott summarized her message as: “If you have a different skin color, you’re going to get relief faster.”

When host Margaret Brennan noted that Harris had not said that, Scott replied, “That’s exactly what she meant.”

Republican Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, whose northern Georgia district saw some damage from Ian, weighed in on Twitter, now known as X. “@KamalaHarris hurricanes do not target people based on the color of their skin. Hurricanes do not discriminate. … Is your husband’s life worth less bc he’s white?””

Any concern about white Floridians being short changed might be misplaced: Out of the $1.1 billion in disaster aid that the Federal Emergency Management Agency provided after Ian, $750 million went to ZIP codes where the population is at least 70 percent white and non-Hispanic, according to an analysis by POLITICO’s E&E News. (Florida’s overall population is 52 percent white.)

Attacks on Harris connecting climate change with equity are no surprise, said Chauncia Willis, executive director of the Georgia-based Institute for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Management, a nonprofit aimed at improving how marginalized communities recover from disasters.

“She was born a target for Republicans,” Willis said. “Everything that she embodies is the antithesis of what the Rick Scotts of the world would like to see.”

Scott communications director McKinley Lewis said in an email: “Senator Scott thinks FEMA should respond to help everyone who needs help in disasters. He is proud to make sure the federal government shows up in emergencies. You should ask VP Harris why she thinks FEMA should re-evaluate how they respond to Americans in need.”

Greene’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

As vice president, Harris was the engine behind many of the Biden administration’s most prominent environmental justice policies.

She played a quiet role in persuading Congress to include $15 billion in Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure law to replace lead drinking water pipes, according to two former administration officials granted anonymity to discuss internal discussions — addressing a health crisis affecting millions of Americans.

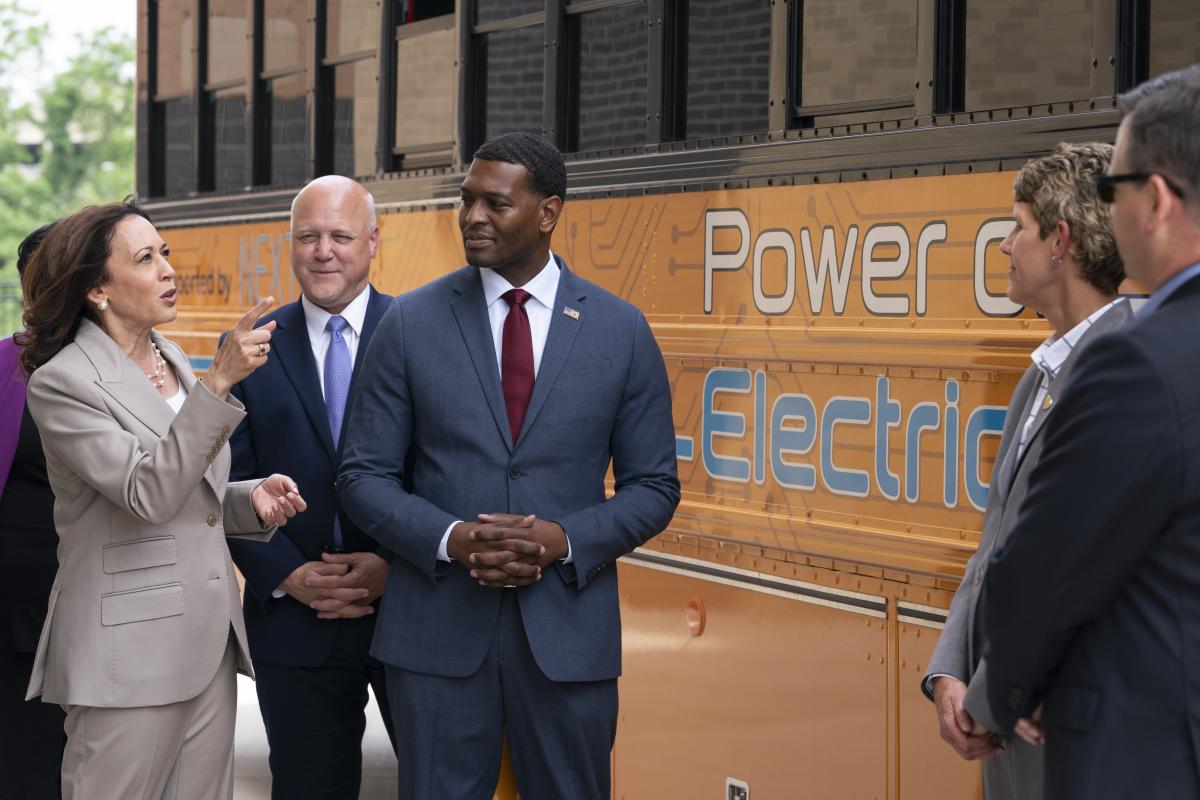

Some administration climate policies aimed at helping low-income and pollution-burdened populations were drawn from legislation such as the Climate Equity Act of 2020, which Harris introduced as a senator from California, and from a spending plan she released while running for president in 2019, EPA Administrator Michael Regan said at a White House event last week.

“I have fought my entire career to address these inequities and advance environmental justice, including here in the White House,” Harris told reporters in December during a call promoting the administration’s policies. On July 22, as she was making the case for her White House candidacy, she talked about her decision as district attorney to go after polluters by launching one of the country’s first environmental justice units.

Beyond her policies, Harris reflects the makeup of environmental justice groups’ grassroots leaders, who are predominantly women of color, said Robert Bullard, a professor at Texas Southern University who is often referred to as the movement’s “godfather.” He called her the “logical choice” to top the Democratic ticket for many reasons.

“When you talk about the on-the-ground in the Black community, it’s Black women. And Black women are the strongest base of the Democratic Party,” said Bullard, who is also a member of Biden’s environmental justice council. “It’s a no-brainer.”

Harris has faced similar criticism, including two days before the 2020 election, when she posteda 50-second animated video on Twitter under the headline, “There’s a big difference between equality and equity.”

A female narrator explains the two terms and says at the end, “Equitable treatment means we all end up at the same place.”

A scholar at the libertarian Cato Institute, quoting the 20th century academic Friedrich Hayek, said in a blog post that Harris was trying to “equalize opportunity,” which the think tank called “totalitarian.”

“Sounds just like Karl Marx,” then-Rep. Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.) tweeted in response to Harris.

Tom Pyle, president of the pro-fossil fuel American Energy Alliance and a critic of the Biden administration’s agenda, is skeptical that Harris’ green credentials will help much with voters.

“Outside of Democratic circles, she’s going to be having to introduce herself or reintroduce herself to the public — and I don’t think you lead with environmental justice in the economy that we have,” he said.

‘Much deeper understanding’

Environmental justice has traditionally been an under-noticed — and much more diverse — part of the green movement, with concerns closer to home than the worries about national parks and endangered species that historically drove the most prominent environmental groups.

Its collections of grassroots groups include low-income, Black, Hispanic or Indigenous activists whose communities bear the ills of smokestacks, pipelines and waste sites in their backyards.

Harris often describes her commitment to environmental justice as a natural extension of her parents’ civil rights work.

When she launched the environmental justice unit in the DA’s office, she argued that “crimes against the environment are crimes against communities, people who are often poor and disenfranchised.” The California environmental group EnviroVoters cited Harris’ record on environmental justice in endorsing her for president.

Harris sponsored environmental justice bills after joining the Senate in 2017, including legislation to ensure that communities long exposed to pollution benefit from federal investments and regulations. A section of Biden’s infrastructure law that gives school districts $5 billion to buy low-polluting buses features language taken verbatim from Harris’ Clean School Bus Act of 2019.

She advocated for federal assistance on behalf of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria demolished the U.S. territory in 2017.

Toward the end of the Trump administration, she sponsored the Environmental Justice for All Act, which would have required permitting decisions to consider cumulative impacts such as climate change and would have slapped a fee on fossil fuels to pay for workforce transition. She was also an early co-sponsor of the Green New Deal, a sweeping but nonbinding resolution backed by some Democrats that called for reducing fossil fuel use and promoting clean energy.

While Biden came into the 2020 campaign trying to understand and address the needs of communities disproportionately affected by pollution, Harris had hands-on experience and had worked with environmental justice activists, said David Kieve, the executive director of the group Environmental Defense Fund Action.

“She started when she was on the ticket from a place of much deeper understanding, both innately and organically, and from her work in the Senate and as California attorney general,” said Kieve, who ran environmental justice outreach for Biden’s 2020 campaign and in the White House.

Harris arrived at the White House just five years after the searing national debate over the lead contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan, where cost-saving decisions by a Republican-appointed emergency manager had exposed the majority-Black and low-income city’s 100,000 residents to extreme levels of the neurotoxin.

Biden vowed in his first State of the Union address to replace every lead drinking water pipe in the country. But Harris took a lead in working with lawmakers to get $15 billion into the bipartisan infrastructure law to fund the work, the two former administration officials said.

In the fall of 2021, Harris announced the administration’s plan to use its regulatory power to require the removal of all lead pipes, then embarked on a tour of some of the country’s most lead-contaminated cities, including Milwaukee and Newark. When that aggressive — and expensive — proposal faced pushback from other quarters of the administration, she intervened behind the scenes to ensure it was released, one of the former Biden administration officials said.

Ike Irby, a senior adviser to Harris on environmental issues since she joined the Senate, said Harris was “really being intentional about finding ways that we can make sure that the communities that have been dumped on and have not had a voice in how the federal government was engaging on different issues were brought into the process.”

Her work on lead contamination could be a political advantage in a handful of the most crucial electoral states, including Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, that are home to some of the country’s largest concentrations of lead pipes. Her messaging on the issue has emphasized not just public health but also the blue-collar jobs created by replacing pipes.

These activists have expressed gratitude for Harris’ visits to hard-hit communities and happiness with the billions of dollars earmarked for environmental justice in the Inflation Reduction Act and other Biden-era laws, as well as regulatory efforts such as EPA’s crackdown on cancer-causing chemicals. But they have also clashed with the administration.

A Biden program called Justice40 set a goal that 40 percent of the benefits of federal spending on clean energy, efficiency and other initiatives should go to marginalized communities. But some members of the White House’s environmental justice advisory council have criticized the administration over its vague definition of what constitutes benefits and pushed for a more concrete commitment on spending levels.

Activist groups also bristled when the White House did not directly include race as a criterion in guiding resources. The administration said it was concerned about legal challenges, but advocates argued that race goes to the core of any environmental justice effort.

GOP lawmakers, meanwhile, have tried to cut the funding for Biden’s environmental justice efforts.

“Part of the challenge of the next few years is going to be defending the progress that we made and ensuring that we are able to continue on that progress,” Irby said.

EMEA Tribune is not involved in this news article, it is taken from our partners and or from the News Agencies. Copyright and Credit go to the News Agencies, email news@emeatribune.com Follow our WhatsApp verified Channel