He held his meetings in Nashville churches, in Black houses of worship that underscored his commitment to God and to godliness. His pupils were largely students, kids from local colleges, some with names — Diana Nash, John Lewis, C.T. Vivian — that would eventually be recorded in the annals of the modern Civil Rights Movement.

Many of them were out-of-towners who’d descended on Middle Tennessee to attend its historically Black schools — Fisk, Tennessee A&I, et al — and become part of a rich Black community that had always been present, even as it was continually pushed to the margins.

These students brought differing perspectives to the matter of race and race relations in Middle Tennessee. Some, from further south, viewed Nashville’s racism as a more mellow sort; others, from up north, were appalled by how willingly Black folks seemed to adhere to an oppressive racial “etiquette.” Ultimately, everyone understood that a follow-up to the Montgomery bus boycott was needed to maintain Movement momentum. They agreed Nashville as the ideal location to launch those efforts, both to secure local wins and catalyze national action.

But it was the proposed nonviolent approach that garnered skepticism.

Embracing a philosophy of nonviolence meant denying oneself

This, the teacher understood. He’d traveled the same road to enlightenment himself. He’d once been a young boy enraged by an ugly slur, shaken when the word sliced into his chest and wrapped vice-like tentacles around his heart.

He’d given in to his flesh that day — the aching, burning flesh that demands an eye for an eye, your pain for mine. He smacked that smirking kid clean across his face, the retribution sweet, if short-lived.

“What good did that do?” his mother asked later, while standing at the kitchen stove. His flesh had cooled by then—the pleasure of payback is always too fleeting—and the boy didn’t have an answer.

Because of this, he could, years later, guide his students as they embarked on their journeys. They learned about others who’d denied their flesh — Mohandas Gandhi, Jesus — before making the courageous decision to deny their own.

There is no ‘both-sidesing’ racism

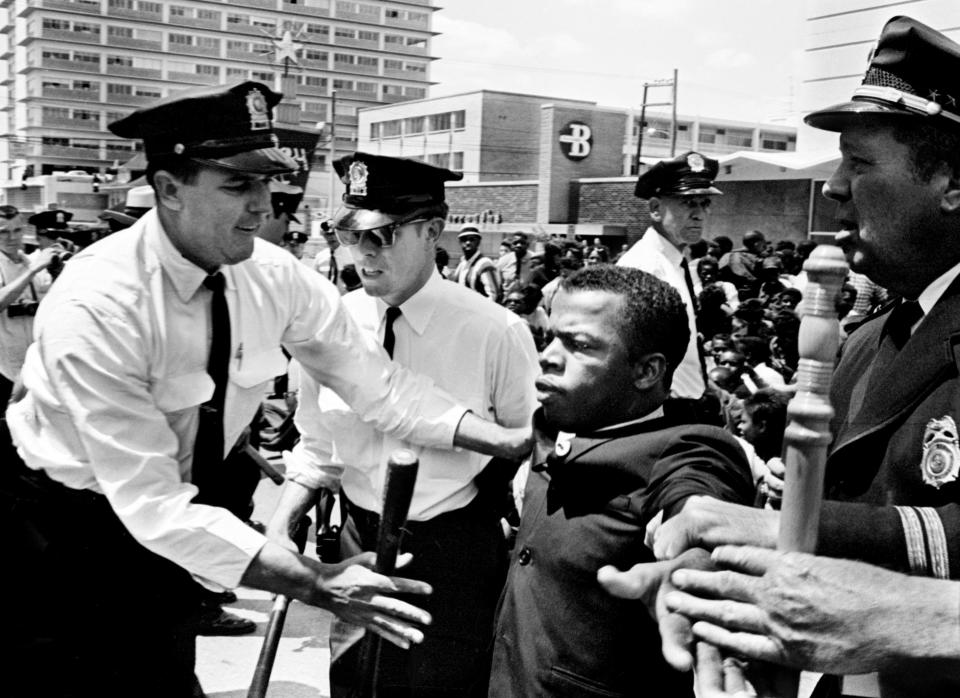

Later, the teacher would say that he was “scared to death” before they took seats at the segregated lunch counters of downtown Nashville. Their target had been chosen by the Black women among them, those impacted by both gender and racial oppression. Still, even the men knew that the most well-designed workshop exercises would pale next to the real-time ache from a white cop’s billy club, or the burn when an white civilian pressed a lit cigarette into bare skin.

The nonviolent strategy had been as brilliant as it was harrowing and Divine. The approach didn’t just bolster the participants belief in their own humanity, or their belief in a God who would faithfully defend it. It introduced that humanity to others, to people all around the country — nay, the world — who watched in slack-jawed horror as white Nashvillians hurled themselves at innocents who refused to respond with their own vitriol.

There would be no both-sidesing this issue.

Even white moderates who’d been content to let racial tensions work themselves out (or not) began to realize there was only one “side,” and it was evil. The bombing of the home of Nashville civil rights attorney Z. Alexander Looby on April 19, 1960, only confirmed this.

Within months, Nashville became the first southern city to desegregate public spaces. It is for this reason that, on the evening of April 19, Martin Luther King, Jr. declared the sit-ins “the best organized and most disciplined in our Southland” during a speech at a speech at Fisk. It’s also one of the prevailing reasons we celebrate and honor James Lawson, the architect of those demonstrations.

Far removed from the boy who was called the n-word and sought his own vengeance, Lawson became a shining example of principle and discipline. He shared his faith and lived it daily, placing people—humanity—above our collective sins.

But now, following his death on June 9, we must mourn Lawson. And as we do, we must remember.

Was the nonviolent movement of the 1960s a failure? Not quite

Something happened in the years following those first cracks in Nashville’s segregated veneer: The city, aware as it was of its image on the national stage, sought to save face.

“Nashville, in the rolling green hills of Middle Tennessee, is a city of colleges and churches,” read The Tennessean on May 21, 1963, “and one thing it cannot abide is unpleasantness. It values peace and quiet as Birmingham, to the south, values separate water fountains and defiance.”

Never mind that integration had been uneven and incomplete, that local courts were still teeming with lawsuits attempting to prevent Black kids trapped in the worst schools in the city, that Black men and women were still locked out of the city’s best jobs.

In fact, C.T. Vivian, one of Lawson’s early students, would go as far as saying that the Movement of the 1960s was largely a failure.

“We would achieve the removal of some discriminatory legislation, only to find that discrimination continued,” he wrote in his book Black Power and the American Myth. “We would win the passage of a new law, only to see it go unenforced.”

I pointed out data showing Nashville’s public education deficiencies. Critics got angry

I don’t think Lawson wouldn’t use the world failure. He would, however, say that the Movement’s efforts were incomplete. They were incomplete then, and they’re certainly incomplete now.

Today, injustice doesn’t look like dynamite bombings and men in white hoods, “colored only” water fountains and whites-only swimming pools. But In Nashville (and far beyond), we need only look around us — at the education gap, the health gap, the wealth gap, and all the other gaps still separating white and Black — to understand that it remains.

And, hopefully, to remember.

If we are to truly honor Lawson, we must remember to not return pain for pain, rebuke for rebuke. The fight for must justice must evolve, just as injustice, itself has evolved. Nonviolence, though far from a passive endeavor, must be met with deliberate action, including collaboration, resource pooling, and, most important, a courage to call out injustice right where it its.

Then, in the searing heat of hate, we need only stand firm in our humanity, and our convictions.

We need only to lead with love — and trust that evil will make itself known.

Andrea Williams is an opinion columnist for The Tennessean and curator of the Black Tennessee Voices initiative.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: James Lawson, teacher of nonviolent action, needs us to keep working

EMEA Tribune is not involved in this news article, it is taken from our partners and or from the News Agencies. Copyright and Credit go to the News Agencies, email news@emeatribune.com Follow our WhatsApp verified Channel